What are you looking for?

Classical Elements

Elements

The Elements, in many philosophies and religious views, are said to be the simplest essential parts and principles of which everything consists. In ancient thought (such as the Greek, Hindu and Buddhist) there is reference to four elements (Earth, Water, Air, and Fire), sometimes including a fifth element or quintessence called Aether or Akasha (space). Ancient cultures in Greece, Persia, Babylonia, Japan, Tibet, and India had all similar lists, sometimes referring in local languages to “air” as “wind” and the fifth element as “void”.

The Chinese Wu Xing system lists Wood (木 mù), Fire (火 huǒ), Earth (土 tǔ), Metal (金 jīn), and Water (水 shuǐ), though these are described more as energies or transitions rather than as types of material.

In the Theosophical literature there is mention to one ultimate element that differentiate in seven, although only four are completely manifested at this stage of evolution.[1]

To govern elementary spirits and thus become king of the occult elements, we must first have undergone the four ordeals of ancient initiations; and seeing that such initiations exist no longer, we must have substituted analogous experiences, such as exposing ourselves boldly in a fire, crossing an abyss by means of the trunk of a tree or a plank, scaling a perpendicular mountain during a storm, swimming through a dangerous whirlpool or cataract. A man who is timid in the water will never reign over the Undines; one who is afraid of fire will never command Salamanders; so long as we are liable to giddiness we must leave the Sylphs in peace and forbear from irritating Gnomes; for inferior spirits will only obey a power which has overcome them in their own element. When this incontestable faculty has been acquired by exercise and daring, the word of our will must be imposed on the elements by special consecrations of air, fire, water and earth.[20]

History

Ancient Greece

In Western thought, the four elements earth, water, air, and fire as proposed by Empedocles (5th century BC) frequently occur.[3] In ancient Greece, discussion of the elements in the context of searching for an arche (“first principle”) predated Empedocles by several centuries. For instance, Thales suggested in the 7th century BCE that water was the ultimate underlying substance from which everything is derived; Anaximenes subsequently made a similar claim about air. However, none before Empedocles proposed that matter could ultimately be composed of all four elements in different combinations of one another.[3] Later on, Aristotle added a fifth element to the system, which he called aether.

Persia

The Persian philosopher Zarathustra (600-583 BCE), also known as Zoroaster, described the four elements of earth, water, air and fire as “sacred,” i.e., “essential for the survival of all living beings and therefore should be venerated and kept free from any contamination”. [4]

Cosmic elements in Babylonia

In Babylonian mythology, the cosmogony called Enûma Eliš, a text written between the 18th and 16th centuries BC, involves four gods that we might see as personified cosmic elements: sea, earth, sky, wind. In other Babylonian texts these phenomena are considered independent of their association with deities,[5] though they are not treated as the component elements of the universe, as later in Empedocles.

Hindiusm

The system of five elements are found in Vedas, especially Ayurveda, the pancha mahabhuta, or “five great elements”, of Hinduism are bhūmi (earth),[6] ap or jala (water), tejas or agni (fire), marut, vayu or pavan (Air or wind) and vyom or shunya (space or zero) or akash (aether or void).[7] They further suggest that all of creation, including the human body, is made up of these five essential elements and that upon death, the human body dissolves into these five elements of nature, thereby balancing the cycle of nature.[8]

The five elements are associated with the five senses, and act as the gross medium for the experience of sensations. The basest element, earth, created using all the other elements, can be perceived by all five senses — (i) hearing, (ii) touch, (iii) sight, (iv) taste, and (v) smell. The next higher element, water, has no odor but can be heard, felt, seen and tasted. Next comes fire, which can be heard, felt and seen. Air can be heard and felt. “Akasha” (aether) is beyond the senses of smell, taste, sight, and touch; it being accessible to the sense of hearing alone. [9][10][11]

Buddhism

In the Pali literature, the mahabhuta (“great elements”) or catudhatu (“four elements”) are earth, water, fire and air. In early Buddhism, the four elements are a basis for understanding suffering and for liberating oneself from suffering. The earliest Buddhist texts explain that the four primary material elements are the sensory qualities solidity, fluidity, temperature, and mobility; their characterization as earth, water, fire, and air, respectively, is declared an abstraction — instead of concentrating on the fact of material existence, one observes how a physical thing is sensed, felt, perceived.

The Buddha’s teaching regarding the four elements is to be understood as the base of all observation of real sensations rather than as a philosophy. The four properties are cohesion (water), solidity or inertia (earth), expansion or vibration (air) and heat or energy content (fire). He promulgated a categorization of mind and matter as composed of eight types of “kalapas” of which the four elements are primary and a secondary group of four are color, smell, taste, and nutriment which are derivative from the four primaries.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997) renders an extract of Shakyamuni Buddha’s from Pali into English thus:

Just as a skilled butcher or his apprentice, having killed a cow, would sit at a crossroads cutting it up into pieces, the monk contemplates this very body — however it stands, however it is disposed — in terms of properties: ‘In this body there is the earth property, the liquid property, the fire property, & the wind property.’[12]

Tibetan Buddhist medical literature speaks of the Panch Mahābhūta (five elements).[13]

Chinese (Wu-Xing)

In Chinese philosophy the universe consists of heaven and earth. The five major planets are associated with and even named after the elements: Jupiter 木星 is Wood (木), Mars 火星 is Fire (火), Saturn 土星 is Earth (土), Venus 金星 is Metal (金), and Mercury 水星 is Water (水). Also, the Moon represents Yin (陰), and the Sun 太陽 represents Yang (陽). Yin, Yang, and the five elements are associated with themes in the I Ching, the oldest of Chinese classical texts which describes an ancient system of cosmology and philosophy. The five elements also play an important part in Chinese astrology and the Chinese form of geomancy known as Feng shui.

The doctrine of five phases describes two cycles of balance, a generating or creation (生, shēng) cycle and an overcoming or destruction (克/剋, kè) cycle of interactions between the phases.

Generating

- Wood feeds fire;

- Fire creates earth (ash);

- Earth bears metal;

- Metal collects water;

- Water nourishes wood.

Overcoming

- Wood parts earth;

- Earth absorbs water;

- Water quenches fire;

- Fire melts metal;

- Metal chops wood.

There are also two cycles of imbalance, an overacting cycle (乘,cheng) and an insulting cycle (侮,wu).

Greece

The ancient Greek concept of four basic elements, these being earth (γῆ gê), water (ὕδωρ hýdōr), air (ἀήρ aḗr), and fire (πῦρ pŷr), dates from pre-Socratic times and persisted throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, deeply influencing European thought and culture. The four classical elements of Empedocles and Aristotle illustrated with a burning log. The log releases all four elements as it is destroyed. The four classical elements of Empedocles and Aristotle illustrated with a burning log. The log releases all four elements as it is destroyed.

Sicilian philosopher Empedocles (ca. 450 BC) proved (at least to his satisfaction) that air was a separate substance by observing that a bucket inverted in water did not become filled with water, a pocket of air remaining trapped inside.[14] Prior to Empedocles, Greek philosophers had debated which substance was the primordial element from which everything else was made; Heraclitus championed fire, Thales supported water, and Anaximenes plumped for air.[14] Anaximander argued that the primordial substance was not any of the known substances, but could be transformed into them, and they into each other.[14] Empedocles was the first to propose four elements, fire, earth, air, and water.[14] He called them the four “roots” (ῥιζώματα, rhizōmata).

Plato seems to have been the first to use the term “element (στοιχεῖον, stoicheîon)” in reference to air, fire, earth, and water.[14] The ancient Greek word for element, stoicheion (from stoicheo, “to line up”) meant “smallest division (of a sun-dial), a syllable”, as the composing unit of an alphabet it could denote a letter and the smallest unit from which a word is formed.

In On the Heavens, Aristotle defines “element” in general:

An element, we take it, is a body into which other bodies may be analysed, present in them potentially or in actuality (which of these, is still disputable), and not itself divisible into bodies different in form. That, or something like it, is what all men in every case mean by element.[15]

In his On Generation and Corruption,[16] Aristotle related each of the four elements to two of the four sensible qualities:

- Fire is both hot and dry.

- Air is both hot and wet (for air is like vapor, ἀτμὶς).

- Water is both cold and wet.

- Earth is both cold and dry.

A classic diagram has one square inscribed in the other, with the corners of one being the classical elements, and the corners of the other being the properties. The opposite corner is the opposite of these properties, “hot – cold” and “dry – wet”.

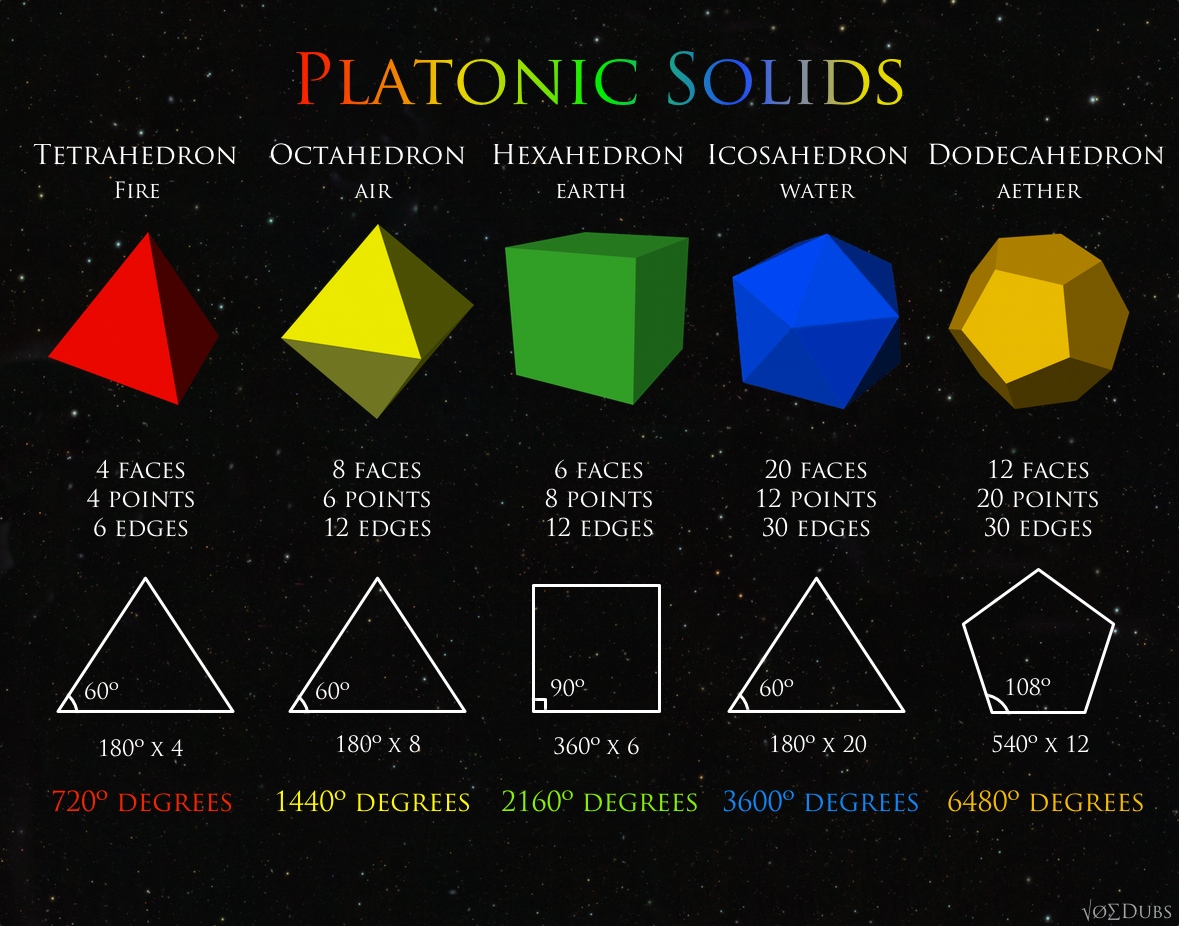

Aristotle added a fifth element, aether (αἰθήρ aither), as the quintessence, reasoning that whereas fire, earth, air, and water were earthly and corruptible, since no changes had been perceived in the heavenly regions, the stars cannot be made out of any of the four elements but must be made of a different, unchangeable, heavenly substance.[16] It had previously been believed by pre-Socratics such as Empedocles and Anaxagoras that aether, the name applied to the material of heavenly bodies, was a form of fire. Aristotle himself did not use the term aether for the fifth element, and strongly criticised the pre-Socratics for associating the term with fire. He preferred a number of other terms that indicated eternal movement, thus emphasising the evidence for his discovery of a new element.[17] These five elements have been associated since Plato’s Timaeus with the five platonic solids.

Astrology and the classical elements

Astrology has used the concept of classical elements from antiquity up until the present. Most modern astrologers use the four classical elements extensively, and indeed it is still viewed as a critical part of interpreting the astrological chart. The elemental rulerships for the twelve astrological signs of the zodiac are as follows:

Fire — 1 – Aries; 5 – Leo; 9 – Sagittarius

Earth — 2 – Taurus; 6 – Virgo; 10 – Capricorn

Air — 3 – Gemini; 7 – Libra; 11 – Aquarius

Water — 4 – Cancer; 8 – Scorpio; 12 – Pisces

The elemental rulerships for the twelve astrological signs of the zodiac (according to Marcus Manilius) are as follows:

Fire — Aries, Leo, Sagittarius – hot, dry, ardent

Earth — Taurus, Virgo, Capricorn – heavy, cold, dry

Air — Gemini, Libra, Aquarius – light, hot, wet

Water — Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces – wet, soft, cold

In Western tropical astrology, there are always 12 astrological signs; thus, each element is associated with 3 signs of the Zodiac which are always located exactly 120 degrees away from each other along the ecliptic and said to be in trine with one another.

Beginning with Aries the first sign which is a Fire sign, the next in line Taurus is Earth, then to Gemini which is Air, and finally to Cancer which is Water — in Western astrology the sequence is always Fire, Earth, Air, & Water in that exact order. This cycle continues on twice more and ends with the twelth and final astrological sign, Pisces. The following list should allow one to visualize this cycle better:

1 _ Aries – (Cardinal Fire): assertively, impulsively, selfishly.

2 _ Taurus – (Fixed Earth): resourcefully, thoroughly, indulgently.

3 _ Gemini – (Mutable Air): logically, inquisitively, superficially.

4 _ Cancer – (Cardinal Water): tenaciously, sensitively, clingingly.

5 _ Leo – (Fixed Fire): generously, proudly, theatrically.

6 _ Virgo – (Mutable Earth): practically, efficiently, critically.

7 _ Libra – (Cardinal Air): co-operatively, fairly, lazily.

8 _ Scorpio – (Fixed Water): passionately, sensitively, anxiously.

9 _ Sagittarius – (Mutable Fire): freely, straightforwardly, carelessly.

10 _ Capricorn – (Cardinal Earth): prudently, cautiously, suspiciously.

11 _ Aquarius – (Fixed Air): democratically, unconventionally, detachedly.

12 _ Pisces – (Mutable Water): imaginatively, sensitively, distractedly.

Elements in Theosophy

The Theosophical view maintains that there are seven fundamental elements in nature, which are differentiations of the one element. These seven elements do not manifest on all the planes simultaneously, but progressively as evolution goes on.

The One Element

In The Mahatma Letters, Master KH writes about one element, which is the homogeneous basis of all:

There is but one element and it is impossible to comprehend our system before a correct conception of it is firmly fixed in one’s mind. You must therefore pardon me if I dwell on the subject longer than really seems necessary. But unless this great primary fact is firmly grasped the rest will appear unintelligible. This element then is the — to speak metaphysically — one sub-stratum or permanent cause of all manifestations in the phenomenal universe.[18]

This element is sometimes called Svābhāvat:

You will have first of all to view the eternal Essence, the Swabavat, not as a compound element you call spirit-matter, but as the one element for which the English has no name. It is both passive and active, pure Spirit Essence in its absoluteness, and repose, pure matter in its finite and conditioned state[18]

The one element penetrates the whole space and, in fact, is space itself:

We recognise but one element in Nature (whether spiritual or physical) outside which there can be no Nature since it is Nature itself, and which as the akasa pervades our solar system, every atom being part of itself pervades throughout space and is space in fact, which pulsates as in profound sleep during the pralayas, and [is] the universal Proteus, the ever active Nature during the manwantaras. . . . Consequently spirit and matter are one, being but a differentiation of states not essences. The great difficulty in grasping the idea in the above process lies in the liability to form more or less incomplete mental conceptions of the working of the one element, of its inevitable presence in every imponderable atom, and its subsequent ceaseless and almost illimitable multiplication of new centres of activity without affecting in the least its own original quantity. The one element not only fills space and is space, but interpenetrates every atom of cosmic matter.[18]

This one element is the origin of the different elements known by the ancients:

If the student bears in mind that there is but One Universal Element, which is infinite, unborn, and undying, and that all the rest — as in the world of phenomena — are but so many various differentiated aspects and transformations (correlations, they are now called) of that One, from Cosmical down to microcosmical effects, from super-human down to human and sub-human beings, the totality, in short, of objective existence — then the first and chief difficulty will disappear and Occult Cosmology may be mastered. Metaphysically and esoterically there is but One ELEMENT in nature, and at the root of it is the Deity; and the so-called seven elements, of which five have already manifested and asserted their existence, are the garment, the veil, of that deity; direct from the essence whereof comes MAN, whether physically, psychically, mentally or spiritually considered. The ancients speak of the five cognizable elements of ether, air, water, fire, earth, and of the one incognizable element (to the uninitiates) the 6th principle of the universe — call it Purush Sakti, while to speak of the seventh outside the sanctuary was punishable with death. But these five are but the differentiated aspects of the one.[18]

Manifestation of the elements

The process of cosmic manifestation proceeds gradually, manifesting six of these elements one after the other. Stanza VI.3 says:

Of the Seven (elements)—first one manifested, six concealed; two manifested—five concealed; three manifested—four concealed; four produced—three hidden; four and one tsan (fraction) revealed—two and one half concealed; six to be manifested—one laid aside.[9]

Mme. Blavatsky applies this sloka to the manifestation of the elements on the lowest plane, one at a time, with the succession of Rounds:

Although these Stanzas refer to the whole Universe after a Mahapralaya (universal destruction), yet this sentence, as any student of Occultism may see, refers also by analogy to the evolution and final formation of the primitive (though compound) Seven Elements on our Earth. Of these, four elements are now fully manifested, while the fifth—Ether—is only partially so, as we are hardly in the second half of the Fourth Round, and consequently the fifth Element will manifest fully only in the Fifth Round.[19]

Occult Science recognises Seven Cosmical Elements—four entirely physical, and the fifth (Ether) semi-material, as it will become visible in the air towards the end of our Fourth Round, to reign supreme over the others during the whole of the Fifth. The remaining two are as yet absolutely beyond the range of human perception. These latter will, however, appear as presentments during the 6th and 7th Races of this Round, and will become known in the 6th and 7th Rounds respectively. These seven elements with their numberless Sub-Elements far more numerous than those known to Science) are simply conditional modifications and aspects of the ONE and only Element.

Four elements only are generally spoken of in later antiquity, five admitted only in philosophy. For the body of ether is not fully manifested yet, and its noumenon is still “the Omnipotent Father—Æther, the synthesis of the rest.”

The succession of primary aspects of Nature with which the succession of Rounds is concerned, has to do, as already indicated, with the development of the “Elements” (in the Occult sense)—Fire, Air, Water, Earth. We are only in the fourth Round, and our catalogue so far stops short.[19]

The ordering of the elements mentioned by Mme. Blavatsky coincides with the degree of their spiritual quality. In a letter to Alfred Percy Sinnett, Mahatma K.H. wrote about:

. . . the principles of earth, water, air, fire and ether (akasa) following the order of their spirituality and beginning with the lowest.

The elements can also be seen as the objective aspect of the seven Dhyani-Buddhas:

“These Brâhmanas (the Rishi Prajâpati?), the creators of the world, are born here (on earth) again and again. Whatever is produced from them is dissolved in due time in those very five great elements (the five, or rather seven, Dhyani Buddhas, also called “Elements” of Mankind), like billows in the ocean. These great elements are in every way beyond the elements that make up the world (the gross elements). And he who is released even from these five elements (the tanmâtras) goes to the highest goal.”[19]