What are you looking for?

Karma

Karma

Karma (devanāgarī: कर्म) is a Sanskrit term that “action” or “deed.” In in Hindu, Jain, Buddhist and Sikh religions karma refers to a law that regulates causes and effects.

“Karma is the restoration of a primordial equilibrium disturbed by the action of personal free-will.”[1]

The Buddhist view of all this, the psychobiological evolutionary account known as the “theory of karma,” is very like the Darwinian idea of evolution. The karma theory describes a “great chain of being,” postulating a kinship between all observed species of beings, and a pattern of development of one life form into another. Humans have been monkeys in the past, and all animals have been single-celled animals. The difference in the karma theory is that individuals mutate through different life forms from life to life. A subtle, mental level of life carries patterns developed in one life into the succeeding ones. Species develop and mutate in relation to their environments, and individuals also develop and mutate from species to species. This karmic evolution can be random, and beings can evolve into lower forms as well as higher ones. Once beings become conscious of the process, however, they can purposively affect their evolution through choices of actions and thoughts.[13]

Eastern Commentary on Karma

Pramahansa Yogananda elaborates on the concept of Karma in his different writings as follow[14]:

Karma means material action, that which is instigated by egoistic desire. It sets into motion the law of cause and effect. The action produces a result that binds itself to the doer until the cause is compensated by the appropriate effect, whether forthcoming immediately or carried over from one life to another.

The habits you cultivated in past lives have substantially created your physical, mental, and emotional makeup in this life. You have forgotten those habits, but they have not forgotten you. Out of the crowded centuries of your experiences, your karma follows you. And whenever you are reborn, that karma, consisting of all your past thoughts and actions and habits, creates the kind of physical form you will have—not only your appearance, but your personality traits. It is these individually created past-life patterns that make one person different from another, and account for the great variety of human faces and characteristics. The very fact that you are a woman or a man was determined by your self-chosen tendencies in previous lives.

Karma is the law of action or cosmic justice, based upon cause and effect. Your every act, good or bad, has a specific effect on your life. The effects of actions in this life remain lodged in the subconsciousness; those brought over from past existences are hidden in the superconsciousness, ready like seeds to germinate under the influence of a suitable environment. Karma decrees that as one sows, so must he inevitably reap.

Your failure or sickness or other troubles started with unwise actions in past lives, and the effects of those causes have been brewing within, waiting for the right time to bubble over. Disease, health; failure, success; inequalities, equality; early death, long life—all these are outgrowths of the seeds of actions we have sown in the past. They cause us to come into this world with varying degrees of goodness or evil within us. So even though God made us in His image, no two people are alike; each has used his God-given free choice to make something different of himself. This is why some people suffer for the slightest reason. Others become angry at the least provocation. And there are those who eat endlessly without any self-control. Did God make them that way? No. Each person has made himself the way he is. There would be no justice in this world if God had arbitrarily made us the way we are. I sometimes think God must be watching in amazement this big zoo of human beings here, blaming Him because they have a headache or a stomachache, or are always getting into trouble. Don’t blame God or anyone else if you are suffering from disease, financial problems, emotional upsets. You created the cause of the problem in the past and must make a greater determination to uproot it now.

There may be a million years of actions of past lives pursuing you. That is why an ordinary individual finds himself so helpless to destroy the binding effects of his karma. He feels hopelessly bound by those invisible chains—influences resulting from all the actions he chose to perform in past lives, through free will or through prevailing influences.

Accumulated bad mass karma precipitates wars, diseases, poverty, devastating earthquakes, and other such calamities. During times of prevalent negative vibratory influences, the individual must thus contend not only with his personal karma, but also with the mass karma affecting the planet on which he lives.

In addition to your karma from the past, what are the influences on your present life? World civilization is one of them. In whatever era a man is born, he is influenced by the civilization of that age. If one is born in the eighth century, he is influenced by that century. You are all dressing, for example, according to the present civilization.

Persons who pass their lifetime satisfying the body and gratifying the ego, unaware of the Divine Image in themselves, amass earthly karma or sins. When they die with those unresolved karmic consequences and with unfulfilled earthly desires, they must reincarnate again and again to resolve all mortal entanglements.

Western Commentary on Karma

H. P. Blavatsky defined the notion of Karma as follows:

Karma (Sk.). Physically, action: metaphysically, the LAW OF RETRIBUTION, the Law of cause and effect or Ethical Causation. Nemesis, only in one sense, that of bad Karma. It is the eleventh Nidana in the concatenation of causes and effects in orthodox Buddhism; yet it is the power that controls all things, the resultant of moral action, the meta physical Samskâra, or the moral effect of an act committed for the attainment of something which gratifies a personal desire. There is the Karma of merit and the Karma of demerit. Karma neither punishes nor rewards, it is simply the one Universal LAW which guides unerringly, and, so to say, blindly, all other laws productive of certain effects along the grooves of their respective causations. When Buddhism teaches that “Karma is that moral kernel (of any being) which alone survives death and continues in transmigration” or reincarnation, it simply means that there remains nought after each Personality but the causes produced by it; causes which are undying, i.e., which cannot be eliminated from the Universe until replaced by their legitimate effects, and wiped out by them, so to speak, and such causes—unless compensated during the life of the person who produced them with adequate effects, will follow the reincarnated Ego, and reach it in its subsequent reincarnation until a harmony between effects and causes is fully reestablished. No “personality”—a mere bundle of material atoms and of instinctual and mental characteristics—can of course continue, as such, in the world of pure Spirit. Only that which is immortal in its very nature and divine in its essence, namely, the Ego, can exist for ever. And as it is that Ego which chooses the personality it will inform, after each Devachan, and which receives through these personalities the effects of the Karmic causes produced, it is therefore the Ego, that self which is the “moral kernel” referred to and embodied karma, “which alone survives death.”[2]

Karma being a universal law, its effects cannot be erased by rituals, meditations, or spiritual beings. Mme. Blavatsky wrote:

No Adept of the Right Path will interfere with the just workings of Karma. Not even the greatest of Yogis can divert the progress of Karma or arrest the natural results of actions for more than a short period, and even in that case, these results will only reassert themselves later with even tenfold force, for such is the occult law of Karma and the Nidânas.[3]

In her book The Key to Theosophy, H. P. Blavatsky wrote the following dialogue on the subject:

THEOSOPHIST. According to our teaching all these great social evils, the distinction of classes in Society, and of the sexes in the affairs of life, the unequal distribution of capital and of labour—all are due to what we tersely but truly denominate KARMA.ENQUIRER. But, surely, all these evils which seem to fall upon the masses somewhat indiscriminately are not actual merited and INDIVIDUAL Karma?

THEOSOPHIST. No, they cannot be so strictly defined in their effects as to show that each individual environment, and the particular conditions of life in which each person finds himself, are nothing more than the retributive Karma which the individual generated in a previous life. We must not lose sight of the fact that every atom is subject to the general law governing the whole body to which it belongs, and here we come upon the wider track of the Karmic law. Do you not perceive that the aggregate of individual Karma becomes that of the nation to which those individuals belong, and further, that the sum total of National Karma is that of the World? The evils that you speak of are not peculiar to the individual or even to the Nation, they are more or less universal; and it is upon this broad line of Human interdependence that the law of Karma finds its legitimate and equable issue.

ENQUIRER. Do I, then, understand that the law of Karma is not necessarily an individual law?

THEOSOPHIST. That is just what I mean. It is impossible that Karma could readjust the balance of power in the world’s life and progress, unless it had a broad and general line of action. It is held as a truth among Theosophists that the interdependence of Humanity is the cause of what is called Distributive Karma, and it is this law which affords the solution to the great question of collective suffering and its relief. It is an occult law, moreover, that no man can rise superior to his individual failings, without lifting, be it ever so little, the whole body of which he is an integral part. In the same way, no one can sin, nor suffer the effects of sin, alone. In reality, there is no such thing as “Separateness”; and the nearest approach to that selfish state, which the laws of life permit, is in the intent or motive.[4]

In his book “The center of Cyclone”[12] John. C. Lily elaborates on Karma thoroughly, in one of sections he specifically assert the following:

In order to burn Karma, one must be wide awake, no matter what is happening to one. At no point during an either negative or a positive experience of a high energy level, can one afford to shut off one’s consciousness. If one is going through a pure negative experience, the extreme negative emotion should be allowed to be imprinted on this negative space so that one’s self meta-programmer does not return there. It is only the purest negative experiences that are worth recording to serve as guideposts to avoid this space entirely in the future. By means of pure experience set up in memory, as soon as this negative space starts to operate within one’s self one can do the necessary things to shift to a positive or neutral space.

In a similar fashion, it is necessary during highly positive states lo remember the experiences as positive and rewarding, so they will attract one automatically back lo those spaces. This, too, is part of one’s Karma in the sense that, without essential experiences in the highly positive spaces, one has great difficulty in knowing how to return there. If one has had experiences in the highly positive spaces, it is sufficiently rewarding so that one wishes to return there and one learns the routes.

There is an almost automatic reward system built into each of us in the sense that in the uterus, in childhood, we were in positive states continuously, though not necessarily consciously. We had to be brought out of the positive state in order to see where we were, and to realize that it was punishing to be removed from the positive and rewarding to return there. Kahlil Gibran’s said it as, “To know joy, one must know sorrow.”

To be the Gurdjieffian man, the awake man, a higher level of man is lo stay awake in order to store positively and negatively reinforced experiences. To eventually stay in the higher states, to eventually integrate the higher j states into one’s ordinary life, is the goal of the awake man.

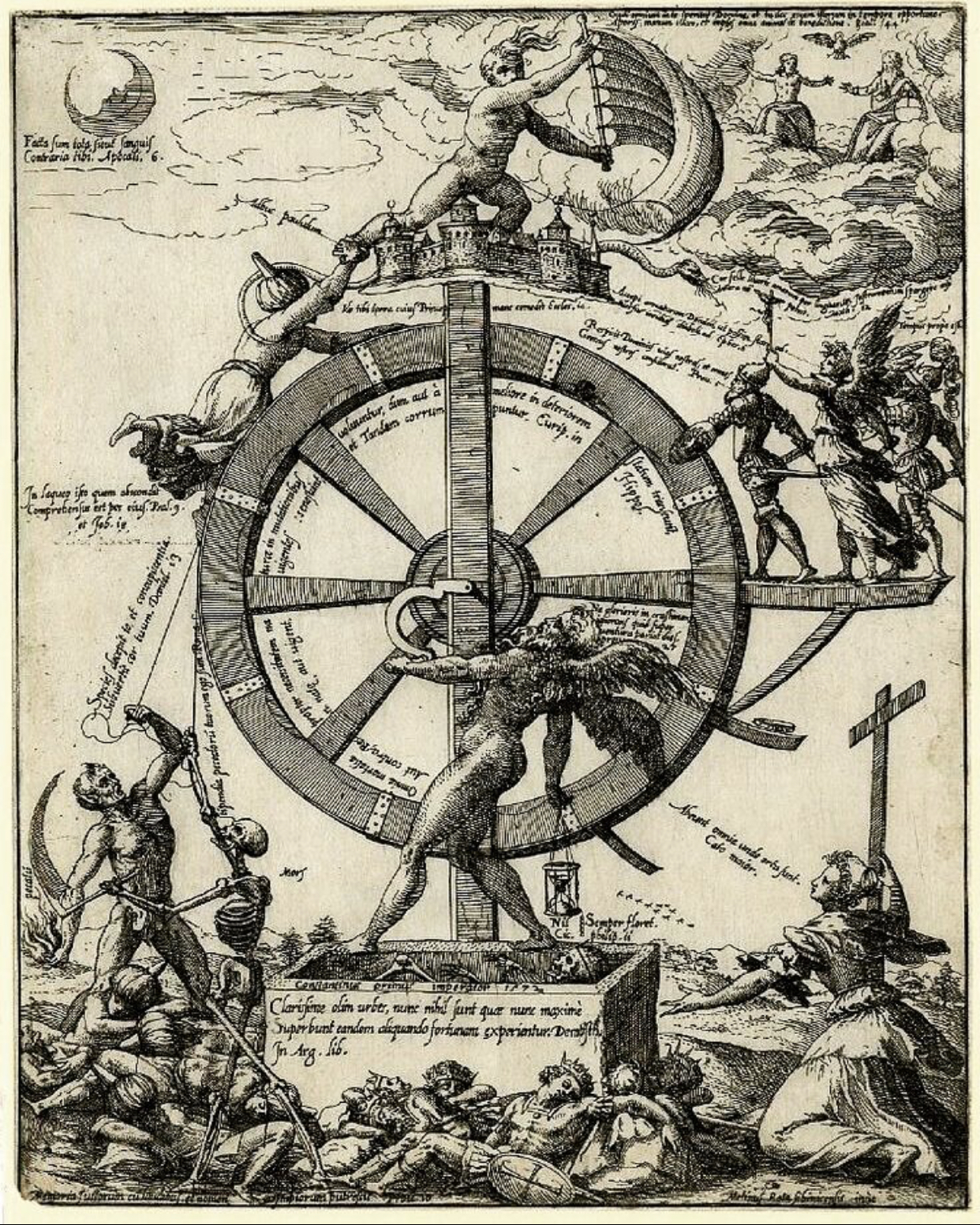

Samsara

Saṃsāra is a Sanskrit/Pali word that means “world”.[5][6] It is also the concept of rebirth and “cyclicality of all life, matter, existence”, a fundamental belief of most Indian religions.[7][8] In short, it is the cycle of death and rebirth.[9][10] Saṃsāra is sometimes referred to with terms or phrases such as transmigration, karmic cycle, reincarnation, and “cycle of aimless drifting, wandering or mundane existence”.[6]

The Saṃsāra doctrine is tied to the karma theory of Hinduism, and the liberation from Saṃsāra has been at the core of the spiritual quest of Indian traditions. The liberation from Saṃsāra is called Moksha, Nirvana, Mukti or Kaivalya.[10][11]

The time of the between, the transition from a death to a new rebirth, is the best time to attempt consciously to affect the causal process of evolution for the better. Our evolutionary momentum is temporarily fluid during the between, so we can gain or lose a lot of ground during its crises. Tibetans are highly aware of this. It is why they treasure the Book of Natural Liberation so much as a guide to bettering their fate.[13]

References

[1]. Claude Bragdon, “Karma Defined” The American Theosophist 65.9 (September 1977), 258. Bragdon noted that he had heard this definition from a young Hindu who had learned it from his master. [2]. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Theosophical Glossary (Krotona, CA: Theosophical Publishing House, 1973), 173-174. [3]. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. XII (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 160-161. [4]. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Key to Theosophy (London: Theosophical Publishing House, [1987]). [5]. Klaus Klostermaier (2010). A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-8011-3. [6]. Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5. [7]. Yadav, Garima (2018), “Abortion (Hinduism)”, Hinduism and Tribal Religions, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, Springer Netherlands, pp. 1–3, doi:10.1007/978-94-024-1036-5_484-1, ISBN 978-9402410365 [8]. Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press. [9]. Rita M. Gross (1993). Buddhism After Patriarchy: A Feminist History, Analysis, and Reconstruction of Buddhism. State University of New York Press. pp. 148. ISBN 978-1-4384-0513-1. [10]. Shirley Firth (1997). Dying, Death and Bereavement in a British Hindu Community. Peeters Publishers. pp. 106, 29–43. ISBN 978-90-6831-976-7. [11]. Michael Myers (2013). Brahman: A Comparative Theology. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-83565-0. [12]. John. C. Lily, The center of Cyclone. [13]. The Tibetan Book of the Dead: Or the After-Death Experiences on the Bardo Plane, According to Lama Kazi Dawa-Samdup. [14]. Pramahansa Yogananda, Karma, Yogananda.com, accessed April 2, 2021.